Every generation rediscovers its anxiety about women painting themselves. This is a story that repeats itself. A woman paints herself. The critics, then as now, lean forward, wagging their fingers and clutching their pearls: narcissism!

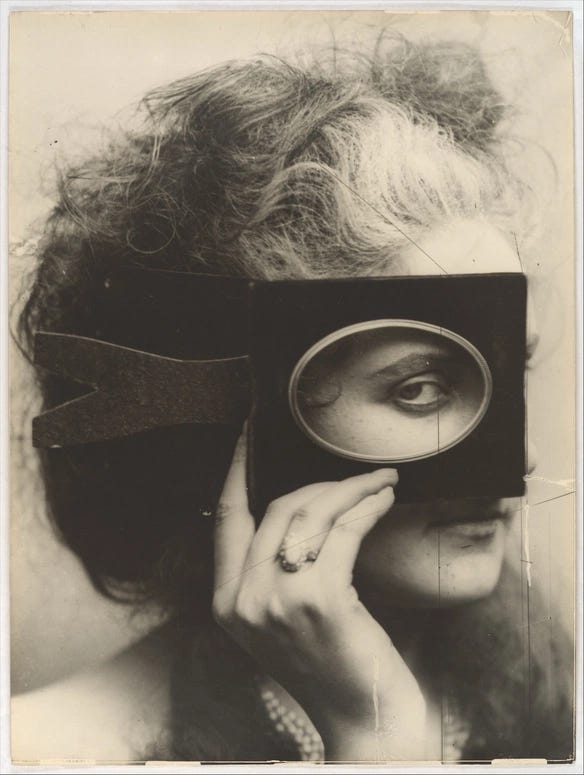

They say the mirror is a trap, the self a prison, the studio a cell. They warn of solipsism, of women turning endlessly inward. It is a story told in a thousand variations, always with the same refrain. But is it true? Or is it, as Jennifer Higgie writes in The Mirror and the Palette, that women painted themselves “for reasons that have nothing to do with vanity, quite the opposite”?

To look into the mirror was not indulgence: the only model available when life classes were barred; the only subject always to hand when commissions were denied; the only body not off-limits.

Catharina van Hemessen paints herself at her easel in 1548. A modest panel, but radical: she inscribes her name, her age, the fact that she, a woman, has painted herself. I exist. I am working. Sofonisba Anguissola paints her own face again and again, the equal, she says, of the Muses and Apelles. Artemisia Gentileschi, with incomparable bravura, casts herself as La Pittura, the allegory of painting itself, something no man could ever claim.

And yet the suspicion lingers. When Rembrandt paints his own face over a lifetime, we call it genius. When Picasso rehearses his own image, we call it legacy. When Lucian Freud paints his battered body, we call it truth. When women do the same, still, we call it vanity.

Why is contemporary self-portraiture by women so often treated as if it were an isolated, narcissistic loop, rather than read within this long lineage of women’s self-portraiture? Why is it still severed from the canon that includes Van Hemessen, Gentileschi, Vigée Le Brun with her daughter, Kahlo reconstructing her body in pain, Gwen John insisting on her presence? To read today’s painters as if they were inventing solipsism afresh is to ignore centuries of women who turned to the mirror not out of self-absorption but out of necessity, defiance, desire.

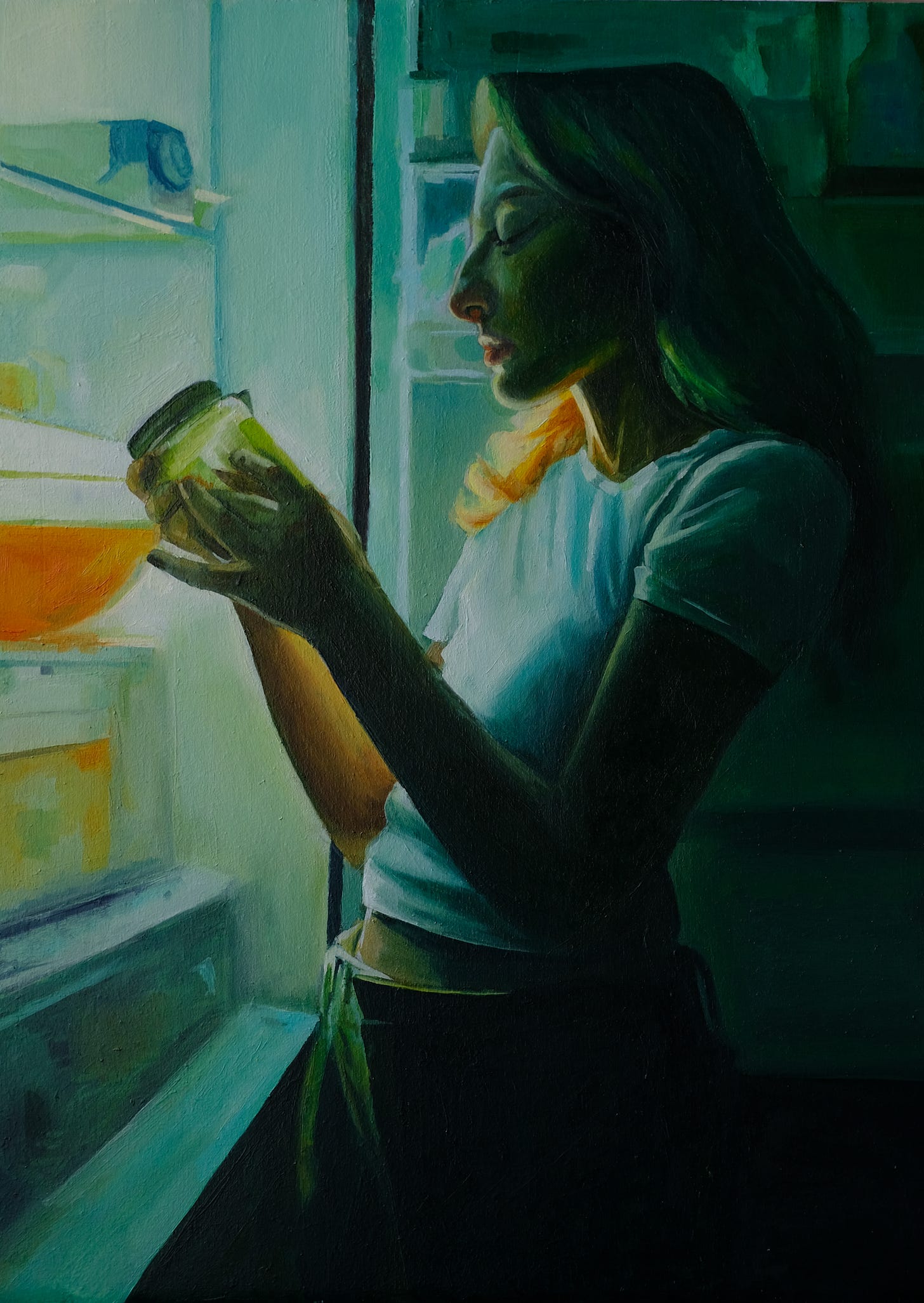

In recent criticism, the claim was made that the real concern is not self-portraiture itself but the cultural trend of women “opting out” of families, and that this absence echoes in the art world, where paintings risk circling endlessly around the self, instead of patriarchy, motherhood, and caregiving. But why must artistic depth be tethered to reproduction or domestic roles? Women artists have always painted themselves under conditions of exclusion — whether mothers or not. Female self portraiture of the past and today confronts “the other” in forms that exceed the family. The mirror is never barren.

The “other,” we are told, is absent now. But is it? Look again. The “other” is everywhere: the gaze that has so often misread women’s bodies, the history that refused them entry, the patriarchy that weighed upon them, the desire and grief and rage that saturate their canvases. In Gwen John’s muted self-portraits, the other is invisibility itself, pressing on her like silence. In Kahlo’s fractured body, the other is illness, politics, betrayal. In Sasha Gordon’s work, the other is queerness refracted, multiplied, made dazzling.

To narrow the “other” to the language of family and romance, to children, to lovers, to domestic ties, and claiming it is lost because these aspects are no longer dominant, is to tether painting once again to the heteronormative script from which women have struggled for centuries to unbind themselves. Such a narrowing is not radical but retrograde. It reduces the vast field of otherness to a household, as though art were only deep when it bends toward reproduction, as though the female painter’s vision must be anchored by marriage or maternity. But the other has always exceeded these bounds. To confine the “other” to the domestic is to miss the very force against which women painted themselves into existence.

In our present moment of hyper-visibility, where women’s images are endlessly branded, swiped, scrolled, the painted self-portrait can look suspiciously like more of the same. But painting moves differently. A selfie is instantaneous; a portrait takes weeks, months. The body must be studied, wrestled with, translated stroke by stroke. This slowness is itself a resistance to the speed of image culture.

Where the scroll demands disappearance, the canvas resists it. Where platforms commodify the self, the brush insists on opacity, density, materiality. Higgie reminds us that “a self-portrait is never one thing” — it can be riddle, protest, survival, prayer. To paint oneself is not to collapse into solipsism, but to open into multiplicity: the self as contested, as haunted, as saturated by the others pressing upon it.

So perhaps the question is not whether women’s mirrors today are narcissistic. Perhaps the question is why women’s self-portraits are still so easily misread as narcissism at all. What unease persists when a woman dares to be both subject and author, muse and painter, image and maker of images?

If there is a crisis, it is not that women no longer know the other. It is that we still cannot see the others already embedded in their work. The unease lies not in the canvas, but in the gaze turned upon it.

In the end, the real provocation of the mirror is not that a woman might be too fascinated by herself. It’s that she dares to insist that her self is worthy of fascination at all.

Wonderfully written and spot on.